In the time of COVID-19

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in in Oklahoma, where five talented early-career journalists are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project is a set of audio and digital stories highlighting the experiences of people whose lives have changed dramatically during the pandemic.

Nancy Barnes is revitalizing her Tsimshian language, Sm’algya̱x, and during the pandemic her group of language learners more than doubled. Lyndsey Brollini reports.

Illustration by Emily Whang

How learning an Indigenous language leads to healing

With a Christmas tree lighting up her dark apartment, Nancy Barnes logs in to join her advanced Tsimshian language class. She’s the first one there, even before the instructor Donna May Roberts.

With university class Mondays and Wednesdays, Tsimshian lullabies on Sundays and Tsimshian games on Fridays, Barnes is learning the Tsimshian language, Sm’algya̱x, almost every day of the week.

Learning Sm’algya̱x has helped Barnes through the pandemic. It keeps her busy so she doesn’t dwell on the rate of COVID-19 infections in Alaska, one of the highest in the U.S.

How learning an Indigenous language leads to healing

Nancy Barnes logs in to her advanced Sm’algya̱x class taught by Donna May Roberts at the University of Alaska Southeast on November 1, 2021. (Photo by Lyndsey Brollini)

“It has saved me in a way that it’s just filled my heart,” she said. “And it keeps me feeling grounded, is the best way that I could explain it. I’ve heard other language learners say the same thing.”

Barnes was lucky. She grew up hearing her grandmother, Clara Ridley, speak Sm’algya̱x. Ridley taught her a few phrases, but Barnes didn’t start learning the Tsimshian language herself until 2003. That year, Sm’algya̱x teacher Donna May Roberts came to Juneau, Alaska to host a language intensive program.

That spurred Barnes to start learning her language, but she wasn’t practicing regularly. Back then, a small group of people would meet in Barnes’ apartment every other week or once a month.

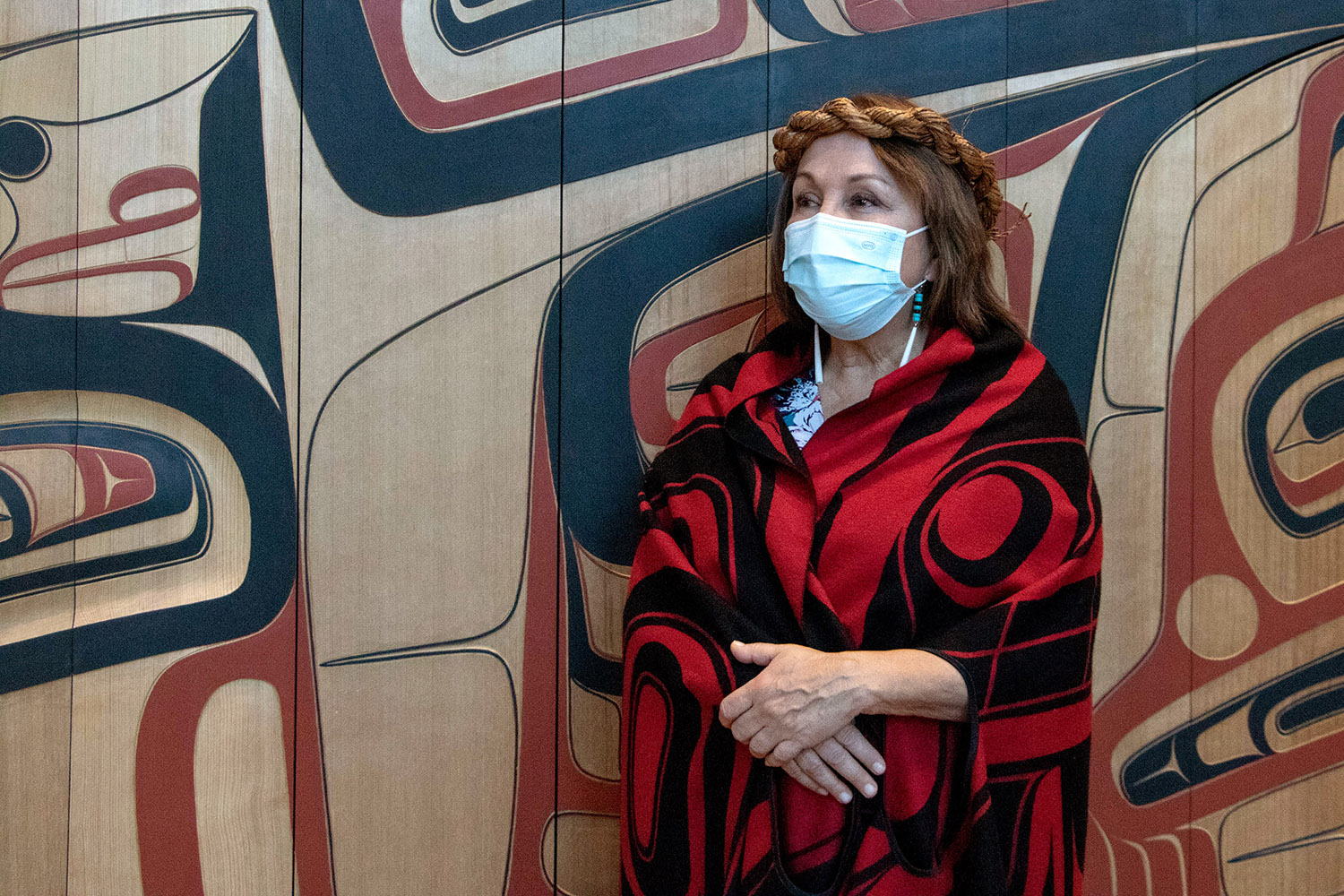

Nancy Barnes at her workplace, the Sealaska Heritage Institute. She’s standing beside a house front carved and painted by David A. Boxley and David R. Boxley. (Photo by Lyndsey Brollini)

In 2015, another Sm’algya̱x teacher David A. Boxley visited Juneau and asked Barnes if she thought anyone locally would be interested in a language intensive program.

“I thought … maybe we’ll get six people that I could get at my place,” Barnes said. “We ended up having… I’m gonna say 30 people. It was too many people for my little apartment.”

A few months after the program, Boxley returned to Juneau and wanted to hold another language session. The Sm’algya̱x learners realized that in a few short months they had forgotten so much. So they formed a group to use the language every Saturday. They almost never cancel a class, even as the pandemic moved everyone online.

In fact, the Juneau Sm’algya̱x learners group grew twice as big, and spans beyond the borders of Juneau to British Columbia, Anchorage, Ketchikan, Metlakatla and Washington state.

“The group got larger, and I would say stronger, because all of a sudden we had all this time,” Barnes said.

Juneau, Alaska on Oct. 4, 2021. (Photo by Lyndsey Brollini)

Even with years of lessons behind her, Barnes still sees herself as a toddler in the language. Through the years, though, she has learned enough to develop a new worldview.

“You see things a little bit different. You know, the words are so descriptive,” Barnes said. “And it seems like every week when we’re doing our Saturday class, I have a lot of those ‘aha’ moments.”

The Tsimshian language is critically endangered, like many Indigenous languages in the U.S. There are just a handful of speakers in Alaska, but there are more in Canada.

“Another reason I think we’re so passionate about this, doing language, is because we know we’re in a crisis situation” said Barnes.

In the past few years, fluent speakers have died. Barnes equates the loss of a fluent Sm’algya̱x speaker to losing a library of knowledge about her language and culture.

In 2003 when Donna May Roberts came to Juneau for a language intensive program, she gave a speech to the learners about the state of Sm’algya̱x. She said that there were only about 30 speakers left in Alaska.

“And I remember feeling that sense of ‘Oh my gosh, we got to keep this up,’” Barnes said. “I would love to have 30 speakers in Alaska right now.”

For those that died during the pandemic, Barnes said she has not been able to properly mourn these losses either. The first thing she wants to do when someone in her community dies is to gather with them. But she can’t.

“I haven’t been able to have the final farewells and comforting those family members and good friends. So that’s really hard,” Barnes said. “I’ve been to a couple of Zoom memorials. And it’s good that we did that. But it’s just not the same as being there in person. But what are we gonna do? We have to keep everybody safe.”

Normally, when someone dies, the family of the deceased hosts a party and invites other clans as guests — there are lots of people, food and dancing. It is also when clans give out Tsimshian names to people. It is similar with the other tribes of Southeast Alaska, Haida and Tlingit too.

Nancy Barnes sings the Tsimshian Happy Song at the boardwalk in downtown Juneau, Alaska on Nov. 3, 2021. Barnes composed the song herself and she sings it often in her dance group Yées Ḵu.oo. (Photo by Lyndsey Brollini.)

There have been a few ceremonies, either small or over Zoom during the pandemic, but to Barnes, they are no substitute for in person gatherings.

“I think that when this [the pandemic] is over, I’m thinking you’re going to just see parties galore,” Barnes said. “Traditional parties and memorials and gatherings and I think we’ll just go crazy with dancing.”

Despite all the loss experienced during the pandemic, Barnes still has hope. Even though gatherings are not happening, Native people have found ways to continue practicing culture and language. To Barnes, it shows how adaptive and resilient her ancestors were.

“And that’s what I keep saying,” Barnes said. “Okay, we can’t do exactly what we’ve been doing, but how do we get around it? And so I think it’s made us stronger.”